School-Based Health Centers

Investigations

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) are touted by proponents as a component of the education trend du jour, “wrap-around services,” which theorizes that if students’ physical and mental health needs are met then academic achievement will improve. Often housed inside of a school, SBHCs feature staff who range from certified nurses to medical doctors and psychologists.

While such programming may seem innocent at first glance, the lack of guardrails on these programs – combined with the existence of parental exclusion policies and low medical age of consent in many states – means that in practice, students can access life-altering treatments without the knowledge of family members. While the majority of SBHCs only offer basic medical care, screenings, and access to behavioral and mental health care, some centers offer students access to abortion (including emergency contraception – such as Plan B) as well as gender-affirming care.

WHAT IS A SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH CENTER?

According to the Community Preventative Services Task Force, a CDC-administered group, School-Based Health Centers “provide primary health services to students in grades K-12 and may be offered on-site (school-based centers) or off-site (school-linked centers).” SBHCs are “often established in schools that serve predominantly low-income communities.”

A goal of SBHCs is to give students and families access to health care and end the cycle of poverty, negative health outcomes, and poor educational achievement.

SBHCs include clinicians who provide “primary care services” or “a multi-disciplinary team providing comprehensive services.” Services vary, but can include “mental health care, social services, dentistry, and health education.” Some SBHCs offer students access to “reproductive health care,” which can include emergency contraception (via the morning after pill).

A 2020 University of Arkansas report casts doubt on the efficacy of SBHCs and the impact on student achievement in a paper that investigated whether “the presence of an SBHC associated with a change in school-level achievement scores for Arkansas public schools,” and “is the presence of an SBHC associated with a change in school-level achievement scores for specific types of schools or specific school populations (i.e. low-income, or majority minority schools)?”

The authors analyzed the “relationship between SBHCs and school-level achievement scores” from 24 schools from across the state, finding that school achievement scores “do not reflect consistent improvement after an SBHC opens on their campus.” The report also notes that according to available data, attendance rates did not improve after the opening of a SBHC on campus.

Overall, their findings reveal “that on average there is no statistically significant relationship between the presence of an SBHC and changes in academic achievement scores.”

A February 2023 clinical research article examining “whether a school-based health center model improved academic achievement compared to usual care” found no “evidence that our SBHC model improved academic achievement,” but did find that SBHCs benefitted “diagnosing and treating children with developmental and mental health disorders.”

Common Services Offered by School-Based Health Centers

- Behavioral Health Services

- Dental Health Services

- Emergency contraception

- Immunization

- Primary Medical Health Services

- Psychiatric Services

- Reproductive Health Care

- Telehealth Services

- Vaccinations

Funding for SHBCs originate from a variety of sources, including government and nonprofit entities. For example, in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ 2023 document Delivering Services in School-Based Settings: A Comprehensive Guide to Medicaid Services and Administrative Claiming, the governmental agency in “consultation with the US Department of Education (ED)” discusses how school districts and SBHCs can navigate services to students who qualify for Medicaid.

The lengthy document highlights that a proposed rule by ED to “modify IDEA Part B requirements” would allow Local Education Agencies (LEAs) to bypass parental consent for IDEA-enrolled children to “access Medicaid payment to support critical services for children with disabilities.”

Medicaid policies vary by state, and some programs dictate that “gender-affirming care” must be covered as medically necessary care for transgender people.

NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS PROMOTING SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH CENTERS

Planned Parenthood

In 2014, Planned Parenthood of New York City (PPNYC) produced a document titled “Priorities for Mayor Bill de Blasio” which states that “schools serve as key entry points for young people to access health care and services they need to stay in school, particularly if they are pregnant or parenting” and that “without access to comprehensive education and services, young people in New York City do not always get the medically accurate information and support of caring adults they need to make decisions about sexual and reproductive health.”

The document called upon the de Blasio Administration to “Ensure continued implementation of the sex education mandate in middle and high schools by augmenting teacher training and incorporating a principal-accountability measure for implementation” and to “increase the number of school-based health centers, supporting initial capital as well as operational costs until they become self-sufficient.”

Planned Parenthood programming is used in K-12 schools under the guise of comprehensive sex education. Spanning elementary through high school, Planned Parenthood covers topics such as birth control, decision making, prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STIs), healthy relationships, consent, and puberty to name a few.

Besides access to abortion, Planned Parenthood also offers “Gender Affirming Care” which includes “estrogen and anti-androgen hormone therapy,” “testosterone hormone therapy,” “puberty blockers,” “surgery referrals,” and “transition support (social, legal).”

School districts found to have past and/or present contracts or Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Planned Parenthood:

Reproduction for All (formerly known as NARAL Pro-Choice America)

A 2016 Reproduction for All (formerly known as NARAL Pro-Choice America) document promoting SBHCs states that the “nation is facing an adolescent reproductive-health crisis.” NARAL claims that by “forcing them [SBHCs] to segregate reproductive-health care from other services would be entirely counterproductive to the basic mission of SBHCs, which is to provide the medical services young people need in an accessible, seamless manner.”

American Federation of Teachers (AFT)

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) supports the inclusion of School-Based Health Centers in schools. The national teachers union claims that SBHCs “improve students’ health outcomes, create supportive learning environments and enhance academic performance.”

AFT membership is not limited to teachers; it also organizes nurses and health professionals. The union is on record stating that “to protect and promote children’s health, the AFT fights to identify and protect school health funding streams” – while failing to note that as the number of SBHC staff grows, union rosters will expand accordingly.

School-Based Health Alliance

The School-Based Health Alliance is a nonprofit that provides “consulting and technical assistance to education to advocacy for policies and funding” to support “school-based health care.” The organization focuses more specifically on “health equity.” The focus on “health equity” is allegedly to help “children and adolescents who unjustly experience health disparities because of their race, ethnicity, family income, where they live, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

The organization explained in a blog that minority children often did not have health care “due to racism and other oppressive systemic societal structures.” A presentation accompanying this blog provides the idea to “screen children from 3 local census tracts with highest social vulnerability for unmet social needs at least twice a year” to “target subgroups of individuals identified on the basis of their membership in a group.” The organization’s presentation also states to “identify patterns of health inequity” by “patient race, ethnicity, and primary (REAL) data” and “patient sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data.

The School-Based Health Alliance also focuses on LGBTQ issues. The nonprofit provided an “eight month virtual learning opportunity for primary care providers in SBHCs” in an effort to “reduce Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) acquisition risk for adolescents.” However, the specific focus was for children “who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning (LGBTQ) or gender non-conforming (GNC).”

In the organization’s 2022 National School-Based Health Care Conference, one presentation addressed the topic “LGBTQ+/BIPOC Youth Connection and Mental Health in the Time of COVID.” The presentation featured a land acknowledgment and targeted families who disagreed with transitioning children to another gender: “During the pandemic and distance learning many teens were stuck isolating with families, blood or otherwise, that did not respect or affirm their sexuality or gender identities.”

The School-Based Health Alliance released a statement on the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, claiming to be “deeply concerned” with the Supreme Court’s decision due to state laws that would restrict abortion because this ruling “will create a climate of fear and anxiety for many women, adolescents, families and health care providers and exacerbate the nation’s existing mental health epidemic.” The nonprofit then stated its support for abortion:

Our vision is that all children and adolescents are healthy and achieving at their fullest potential. We believe that reproductive autonomy is fundamental to this goal and should not be determined by the government.

The organization also has an additional provision statement in support of teaching children about abortion and promoting it as a potential outcome of a pregnancy, if the minors choose to go that route. The organization explains that SBHCs should provide “pregnancy testing and counseling” that will “include the full range of options: continuation of pregnancy, adoption, and elective termination.”

Health Resources and Services Administration

On March 14, 2023, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, hosted a webinar titled “Health Center Excellence in Family Planning.” At the beginning of the session, HRSA Administrator Carole Johnson states that the webinar is part of the HRSA’s efforts to provide “up-to-date clinical recommendations” and “ensure our family planning guidelines and contraceptive guidelines that are both the guidelines that inform clinical practice, but also under the Affordable Care Act, inform access to free preventative services, are up to date and reflect the best practices in clinical guidance.”

Participants in the webinar included members from the HRSA administration, staff from OneWorld Community Health Centers in Omaha, Nebraska, and staff from Blue Ridge Community Health Services in Hendersonville, North Carolina. Both OneWorld and Blue Ridge administer a combined sixteen school-based health centers in local school districts.

Per the webinar transcript, a staff member from Blue Ridge stated: “I’m the State Medical Director of our school-health program. I’m in my school health center right now, so it is definitely, flexibility is a major focus for us. In North Carolina, we cannot distribute any contraception on site at school by law, so we definitely have to do some problem solving sometimes, but we definitely reinforce the education standpoint.”

A member of OneWorld Community Health Centers (which services several campuses in Omaha Public Schools) stated that in Nebraska they “are not able to dispense birth control, nor talk about birth control” but they have “developed two standalone teen and young adult health centers.”

A second OneWorld staff member shared that “one of our strategies was to have one of our school-based health center staff also work in our teen and young adult health center so that the kids know that, hey, there is the lady I just saw at my school is over here and it’s a familiar face and it takes away some of that initial fear.”

Kooth Digital Health

Kooth plc is a publicly traded digital health platform of “clinical psychologists and accredited counsellors” that works with “children and young people who may need advice and signposting, help, more ongoing help or immediate risk support.”

The online mental health platform is an “anonymous site which helps children and young people to feel safe and confident in exploring concerns and seeking professional support.”

Kooth asserts that it “empowers schools to address mental health needs for millions of students internationally.” It makes the following claims:

- “Reducing waiting lists for Behavioral Health services”

- “Extending your hours”

- “Anonymous, data-rich insights”

- “Determining appropriate resource allocation”

- “Decreasing absenteeism and learning loss”

- “Research partnerships”

In March of 2023, the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) announced the launch of its Behavioral Health Virtual Services Platform. The platform will “support the delivery of equitable, appropriate, and timely behavioral health services from prevention to treatment to recovery” and “provide support and resources, such as interactive digital education, self-monitoring tools, application-based games, and mindfulness exercises, as well as offer access to free, on-demand one-on-one coaching and counseling supports.”

The DHCS “selected Kooth to support the delivery of equitable, appropriate, and timely behavioral health services to youth and young adults (ages 13-25).”

Kooth claims that the contract with the state of California had a “$188m minimum value.”

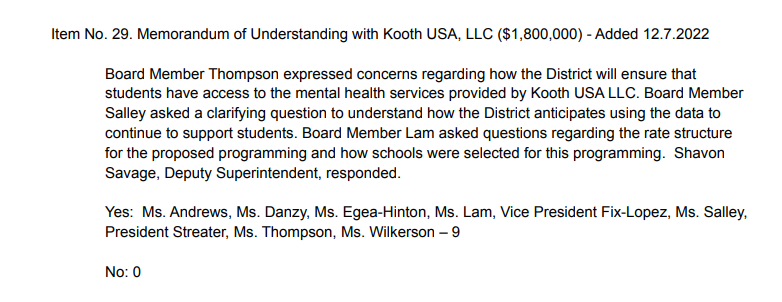

On February 21, 2023, the School District of Philadelphia announced the launch of its partnership with Kooth to offer its students “confidential online mental health support.” The $1,800,000 contract was approved by the board on December 15, 2022.

EXAMPLES OF SCHOOL-BASED HEALTH CENTERS IN OPERATION

California

The San Lorenzo High School-Based Health Center, serving San Lorenzo High School, Arroyo High School, and Sunset High School, “provides medical care including reproductive health services, sports physicals, prevention and treatment of STIs, health education and behavioral health services.”

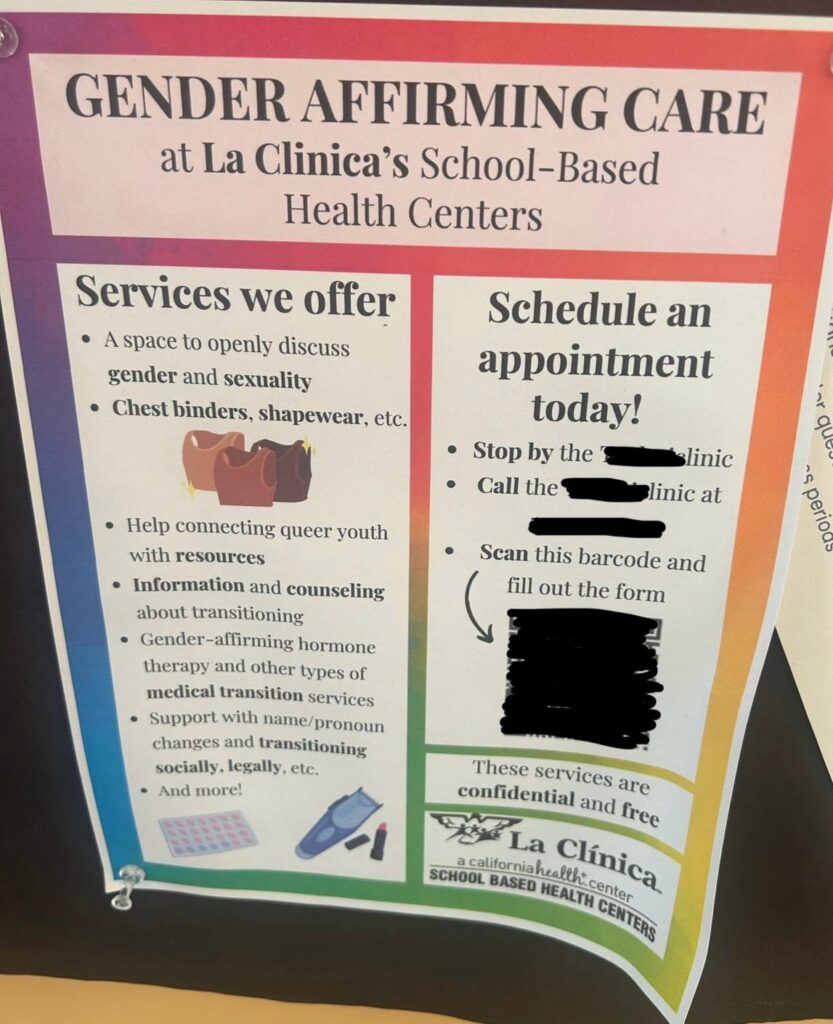

According to a February 28, 2024, post on X (formerly known as Twitter), the SBHC offers students access to “gender affirming care” including “chest binders, shapewear, etc.,” “information and counseling about transitioning,” “gender-affirming hormone therapy and other types of medical transitioning services,” and more.

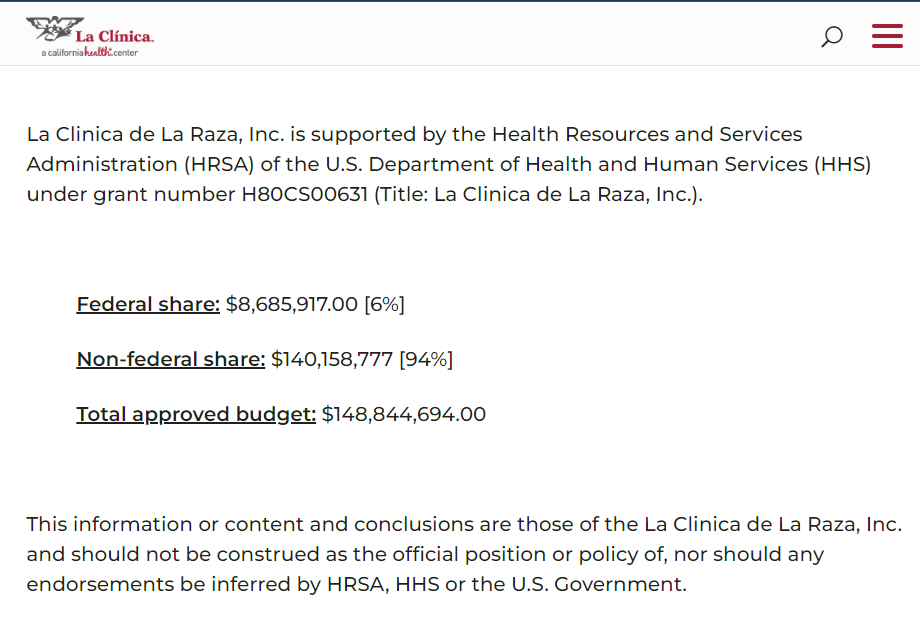

The SBHC is operated by La Clinica de la Raza, Inc., which receives grant funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).

Illinois

The Evanston Township High School Health Center, in partnership with the NorthShore University HealthSytstem and the Evanston Department of Health and Human Services, provides “care for ALL ETHS students, empowering them to take agency of their own health care practices and optimize their lifelong physical and mental health.”

Services provided to the students include:

- Acupuncture

- Gynecologic care

- Vaccinations

- Mental health services

- Reproductive services

- STI Testing and Treatment

On September 23, 2022, the school’s student newspaper published an article, “Getting comfortable with contraception,” which stated that the “hub of reproductive care and information at ETHS” is “right next to your algebra class.”

The article noted that the Health Center has a “one-time consent form, which must be signed by parents to use the clinic for any purpose,” but once signed, students get “full access to use the health center’s services.” According to the reporters, students can get “prescriptions for short-term hormonal birth control like the birth control pill” and “even without the parental consent form students have access to free condoms and Plan B, an emergency contraceptive that can be taken up to 72 hours after sex.”

It concludes that “even though the Health Center provides a variety of forms of medical care, from sports physicals to checkups for minor health issues like sore throats, it still has a reputation as a reproductive care clinic.”

In 2021, the Evanston RoundTable article “In Evanston, abortion access options are limited” featured an interview with health center staff, who stated that they “have worked with students to help them find abortion care, if that is what they are seeking.” The staff members explained that they “as a school-based health center refer to organizations that do abortion, versus hospitals that do not advertise abortion as a service.”

The article stated that the health center staff “provide resources for students to use parental notification judicial bypass programs and abortion funds, like the Chicago Abortion Fund, that offer financial assistance.”

Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s School-Based Health Center Program 2021-2022 Annual Report states that School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) are “health centers that offer a variety of health services, including primary and behavioral health care.”

Services include:

- Primary care

- Vaccinations

- Behavioral health care

- COVID-19 testing

- Dental care

- Collaborative care planning/case management

- Sexual and reproductive health care

- Community engagement

According to the annual report, the SBHCs centered “Racial Equity” by ensuring “equitable access to health care services across all racial/ethnic groups.” The Department of Public Health states that its “SBHC Program prioritizes serving youth and children in communities and populations that have been disproportionately affected by health inequities, including those most affected by racism and poverty.”

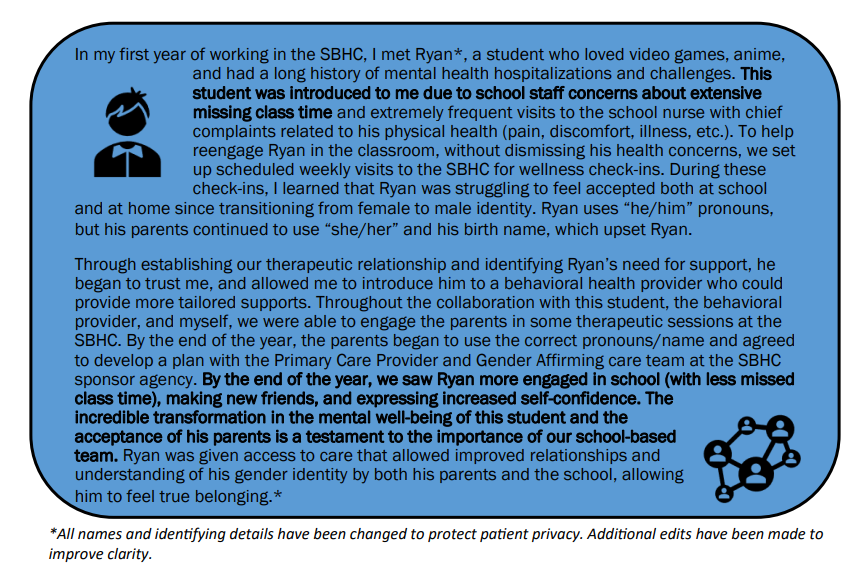

Under the section “A Meaningful Impact,” the report notes that stories come from “MDPH’s SBHC partners that used their unique position to meet the needs of students and their families.” One of the featured stories included the anecdote that “[d]uring these check-ins, I learned that Ryan was struggling to feel accepted both at school and at home since transitioning from female to male identity.” It continued: “Ryan uses ‘he/him’ pronouns, but his parents continued to use ‘she/her’ and his birth name, which upset Ryan.”

The SBHC staff and behavioral provider were “able to engage the parents in some therapeutic sessions” which resulted in the parents beginning to “use the correct pronouns/name and agreed to develop a plan with the Primary Care Provider and Gender Affirming care team at the SBHC sponsor agency.”

Missouri

In St. Louis, the Jennings High School SBHC (the”SPOT Clinic“) mirrors Washington University School of Medicine’s The SPOT. The clinic provides “integrated multi-disciplinary medical health, behavioral health and social services in coordination with community partner organizations.”

Services offered at the SBHC include:

- Routine medical care

- Screening for STIs

- Contraception

- Treatment of Depression and Anxiety

- Health education about sexual and reproductive health issues, asthma, nutrition, stress, etc.

In early 2023, the Washington University Transgender Center at the St. Louis Children’s Hospital came under scrutiny over accusations it was secretly transitioning children. PDE’s Freedom of Information Act requests revealed that a local school district had reached out to the center for advice about whether to inform parents of child chest binder use and what to do about multiple fifth grade students transitioning at the same time.

Dr. Sarah Garwood, the principal doctor at the center of the controversy, was also the medical director of The SPOT at Jennings High School.

New Mexico

On March 30, 2023, New Mexico’s governor signed into law SB 397, “School-Based Health Centers.” The law states that “[s]chool-based health centers shall be established in schools, within the boundaries of school campuses or within safe walking distances from school campuses as determined by the school and the school-based health center operator.”

It also stated that SBHCs shall provide the following:

- Primary health care

- Preventative health care, including comprehensive health assessments and diagnosis

- Treatment of minor, acute and chronic conditions

- Mental health care

- Substance use disorder assessments, treatment and referral

- Crisis intervention

- Referrals as necessary for additional treatment, including inpatient care, specialty care, emergency psychiatric care, oral health care and vision health care services.

Oregon

The Multnomah County Health Department, which services nine schools, has students fill out its “Adolescent Health Assessment” for ages 12-17. The assessment asks minors if they “understand confidentiality (privacy)” regarding their health information; the legal age of consent for medical services without parental involvement in Oregon is 15 years old.

Assessment questions include how much food a student eats, whether they make themselves throw up, if they have “wished” they were “dead” or “could go to sleep and not wake up,” or thought about killing themselves or attempted to. The assessment also asks students as young as 12 if they are attracted to “males,” “females,” “both,” or “none,” and if they “ever felt uncomfortable being identified as male or female.”

It also asks minors if “anyone close to you have guns or weapons” and if anyone “ever hurt, touched or treated you or anyone in your house in a way that made you feel scared or uncomfortable.”

Washington

In 2018, the Families, Education, Preschool, and Promise (FEPP) Levy was approved by Seattle voters that included “a seven-year, $619 million-dollar investment in Seattle’s youth” intended to “achieve educational equity, close opportunity gaps, and build a better future for Seattle students by investing” in programming such as “physical and mental health services that support learning.”

As part of the FEPP Levy’s school-based health investment, funds were included for the “creation of a school-based health center (SBHC) at Nova High School.” The Seattle school partnered with Public Health – Seattle & King County (PHSCK) and Cardea Services to “provide culturally competent and trauma-informed health services, with specific attention to serving LGBTQ+ youth in the school and the broader community.”

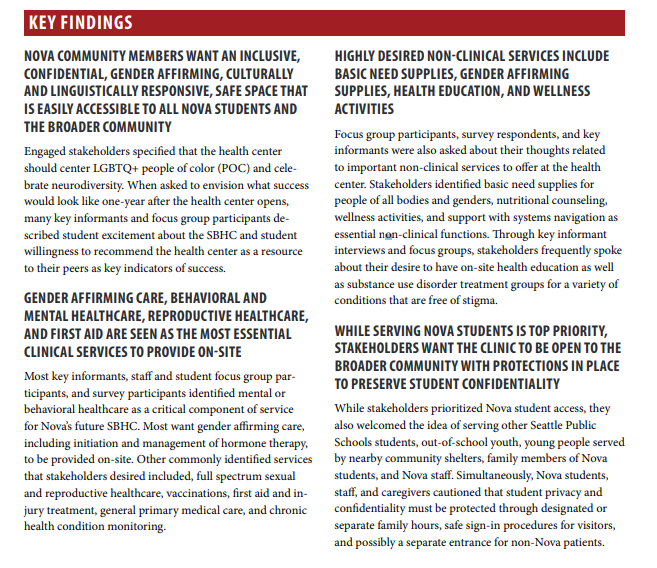

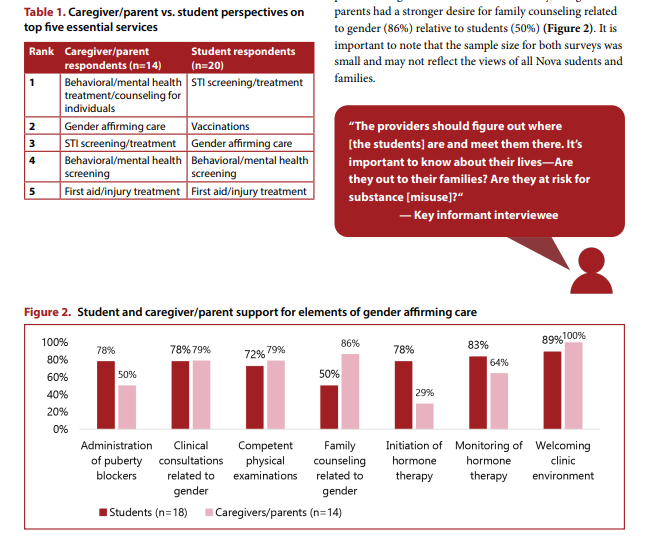

According to the document’s key findings, most informants “want gender affirming care, including initiation and management of hormone therapy, to be provided on-site.”

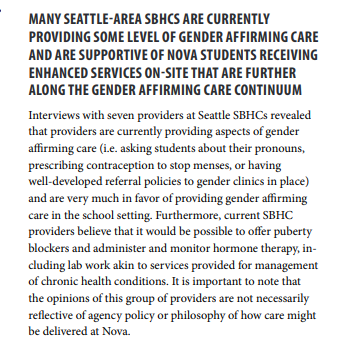

The document also states that “many Seattle-area SBHCs are currently providing some level of gender affirming care and are supportive of Nova students receiving enhanced services on-site that are further along the gender affirming care continuum.” It continues: “Interviews with seven providers at Seattle SBHCs revealed that providers are currently providing aspects of gender affirming care (i.e. asking students about their pronouns, prescribing contraception to stop menses, or having well-developed referral policies to gender clinics in place)” and “current SBHC providers believe that it would be possible to offer puberty blockers and administer and monitor hormone therapy, including lab work akin to services provided for management of chronic health conditions”

Other entities that contributed to the creation of the SBHC include the Gender Clinic at Seattle Children’s Hospital and School-Based Health Alliance.

In July 2023, a PDE report exposed that both Nova High School and Meany Middle School offered “gender affirming care” as part of the medical services offered by SBHCs. The full report can be found here.

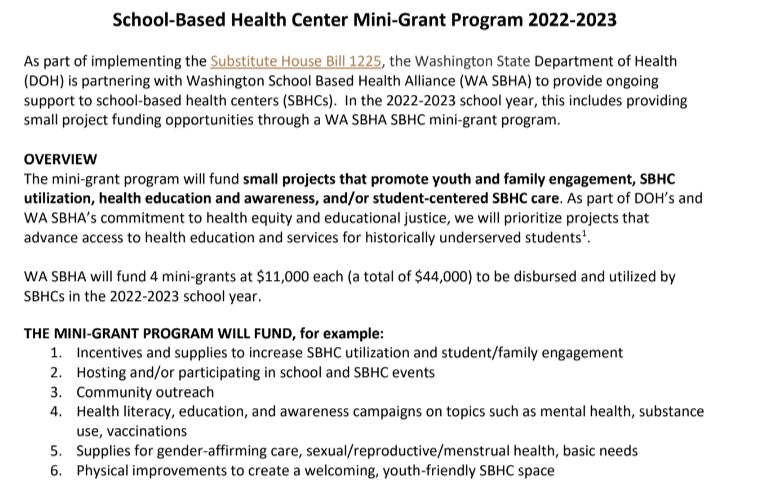

The Washington State Department of Health, in partnership with Washington School Based Health Alliance, offered districts SBHC mini-grants in 2022-2023 through the implementation of Substitute House Bill 1225.

Each mini-grant of $11,000 can be used by a school’s health center for “incentives and supplies to increase SBHC utilization,” for “supplies for gender-affirming care, sexual/reproductive/menstrual health, basic needs,” and “physical improvements to create a welcoming, youth-friendly SBHC space.”

QUESTIONS PARENTS CAN ASK THEIR SCHOOL

- What services are offered through the school-based health center?

- What is the parental notification policy for students to receive services at the school-based health center?

- How is parental consent for minors obtained before students access any type of services at these centers?

- Does the district/school have a clear process posted publicly regarding prior parental consent to access services? If so, where can parents access it?

- Can parents review and approve the types of medical care or treatments their children might receive at these centers?

- What outside organizations provide funding or other assistance to the school-based health center?

- How does the school district ensure that parents have access to relevant information about the school-based health centers and their operations?

- If a student that falls under the mature minor doctrine receives a service or medication that causes negative side effects, who is liable for the outcome?

- Will parents have access to the medical file created at the school-based health center?

- Does the school-based health center offer emergency contraception?

A running list of districts with School-Based Health Centers in operation can be found HERE.

Stay Informed